“For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country … Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700, 000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.” That’s Balfour, writing in 1919.

I’ve been doing a lot of reading in recent weeks, and talked to others who’ve been doing a lot of reading, trying to understand how the Israel / Palestine situation lined up to create the hell currently unfolding. One of the things we find when we compare notes is that there are a lot of books telling totally different stories about it, and a lot that provoke more questions than they answer, leaving glaring gaps in their stories.

Here’s one book that answered some of the questions taxing my brain. There’s an obvious reason why left and right divide over this issue – the left see a racist, colonialist regime applying double standards at a rate unseen since apartheid South Africa. The right see a big money, big tech country with some unreasonable Arabs being difficult and getting in its way. That really is Victorian thinking – or as some right wing politicians will have it, traditional British values.

One of the reasons I recommend Sand’s book is that it presents a detailed and fascinating analysis of the thinking of people such as Balfour, who sound so outrageous to us now, as well as the thinking of the peoples of Europe before, during and after the era of The Balfour Declaration. It also answers my question about why histories of Israel tell widely differing stories – and why the traditional Israeli “left” seems so strange to European socialists.

A key point is that a lot of scholars base their thinking on Israel on antique, if not ancient texts – texts written in a time before mass media or fast, long distance travel. Back then, people simply did not have the perception of a whole country being their “homeland”, or of such a wide area being something they could be expected to defend. Ancient mentions of “my country”, “the land of our fathers”, “the promised land” and similar notions normally were not referring to nearly such large areas as we now habitually think of when we raise flags.

What is socialism?

Another key issue I hadn’t understood before is the history of what passes for socialism in Israel. Sands explains that, as the pre-1948 immigrants to Palestine had good reason – immeasurably good reason in many cases, after World War Two – to carry that dream of a sacred homeland that belonged exclusively to Jewish people. It was people like that who founded and peopled the Kibbutz movement, which many saw as a network of socialist, co-operative communities but, before Israel was a sovereign country, they needed some way of making the communities truly theirs and so, whilst they saw them as egalitarian co-operatives, that philosophy extended only to Jewish people.

It’s never been clear to me whether that stance applies to a religion or a race, and it’s hard to get a definitive answer from those who present as experts on this but – “socialism for us, not for them” is not a unique idea, it’s just almost unique. Most people would say that’s not socialism. Some would give it another name, and point out that that’s a sure-fire way of embedding conflict, and ending badly.

Flag wavers

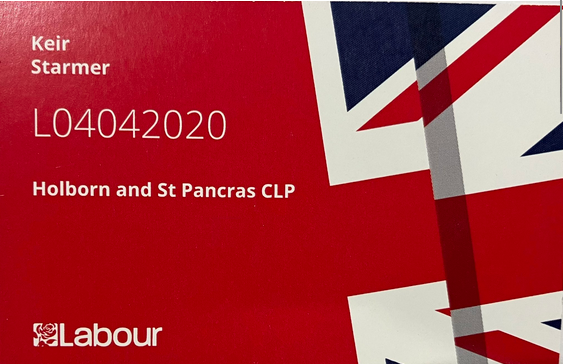

The notion of devotion to the national flag gets some attention too, and for me, clarifies why Keir Starmer’s Labour Party have started draping everything in the national flag, and why that felt like yet another insult to the left.

Socialists tend to be internationalists because they don’t see politics as “my country first”, they see it as “humanity first” and when it comes to entitlement to land, socialists are less impressed by “historic rights” than they are by the labour put in by the people who are now, today, working the land – or on people now living who were thrown off the land for the sake of national-scale projects.

In my own personal view, socialism brings with it respect for people and their environment. Nationalism brings with it colonialism and racism – those Victorian values that glare out of that Balfour quote at the top of this review.

A quick read or a lengthy one?

If you are fascinated by the history of ideas and attitudes, and you really want to understand all the paradoxes and conflicts that have embedded violence and suffering in Israel / Palestine, you’ll enjoy this book. If you’re not mad about lengthy, in depth reads then I recommend borrowing Sand’s book from the library and reading The Conclusion (The Sad Tale of the Frog and the Scorpion) and the Afterword (In Memory of a Village).

That won’t take you long and it’s an engaging, personal and enlightening story, because Sand is a professor of History at Tel Aviv University who became increasingly disturbed by the fact that the bright, new, high-status University he worked in was on the site of something else, something that never got a mention in history books or lectures, nor in the local museums or tourist guides so he went and found out about, and wrote about, the village that used to be there. Along the way, the story makes clear why there are so many disturbing gaps and paradoxes in histories of Israel.

*******************

Dear Reader,

Times are hard, and so the articles on this site are freely available but if you are able to support my work by making a donation, I am very grateful.

Cheers,

Kay

********************