This is the latest result of a favourite pastime of mine. One of the main reasons I still hang onto a library ticket and the habit of walking into actual buildings with actual books in them is the opportunity it gives to meander around and let things you didn’t know you wanted to read catch your eye.

No, filthy online bookstores’ ‘selected for you’ pushes are NOT the same thing.

This is a book about our country’s experience of World War Two, but it’s not like any other that I’ve read. It’s about the actual experience of the actual land – you know, that stuff Scarlett O’Hara was left with a handful of.

War is a strange thing. On the one hand, people don’t like wars so governments have to lie a lot, and employ a lot of totalitarian behaviour to get them to join in; but on the other hand, it’s one of the few times that the average government can be seen actually doing their job (that is, running the country) because you can’t manage a war if you don’t get everything functioning. As a result, what our actual land experienced during the war was probably the nearest thing to socialism that has ever happened in the UK.

People – especially troops and factory workers – needed to be fed, and the threat from German subs to shipping meant the UK had to be darned sure it was producing as much food as it could. That meant the creation of the deceptively inane sounding Agricultural Committees whose job was to deal with land owners who were sitting on property and failing to do anything useful with it. This was an extremely painful experience to the more instinctively entitled of our land owners and, in more than one case, resulted in an actual shoot-out, when a farmer barricaded himself in his farmhouse and defied the police to make him do anything.

There were also, however, many landowners who were surprised and delighted when the ‘Ag Committees’ sent in advisors who showed them just what could be done with their land – not to mention literal armies of ‘land girls’ – women whose lives were transformed by the unexpected opportunity to get out there and make things happen, maintaining and driving tractors, trucks and all kinds of things young women would not have expected to be anywhere near, not to mention getting to know people they never would have known existed otherwise.

Have to admit, I chortled happily along as I read of outraged US servicemen complaining bitterly that the land girls were talking, drinking and dancing with black servicemen, and Brits of a more nervous disposition worrying about how the ‘girls’ got along with Italian and German POWs whilst working in the fields. I laughed even louder at the letters from distressed gentlefolk, outraged at the discovery that country-dwellers who had room were expected to take in evacuees – all of them were expected to, even rich and privileged people. It’s amazing how many stood behind the obvious (to them) defence that one couldn’t possibly take in children in war time because you just couldn’t get the servants to look after them.

Another kind of fun is provided by the incredible stories of those people who were super-secretly lined up to be our underground resistance army, should the threatened invasion become a reality. They had all kinds of ingenious fun building bunkers and dugouts, converting caves and natural features, figuring out how to live – literally underground in many cases, invisibly in the countryside, standing ready to emerge and fight back when called upon. Many of their creations were found by kids years after the war, and became real-life hideouts for those kids’ imaginary adventures in the woods.

The hideouts for our national art treasures were on a much grander scale and included extensive underground buildings in, for example, old slate mines, where storage vaults could be air-conditioned and ensured far away from potential war damage. Not so entertaining were the underground weapon and explosives stores, which in one case caused the largest non-nuclear detonation the world had ever seen at that time, ripping through the surface and completely pulverising a farmhouse along with quite a few people and cows who were unfortunate enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

There was also extensive damage to both land and historic buildings wreaked by the vast numbers of troops, vehicles and aircraft constantly moving in and out of and throughout Britain in the latter part of the war, changing landscapes, transforming the lives and experiences of many villages and, ultimately, changing the nature of life in this country forever.

This book is an eye-opener in many ways, and positively fills your head with ‘what if…?’s. It was the spectacular display of the ‘can do’ attitude that drove the Attlee revolution, giving us our NHS, our council housing stock, our extensive education infrastructure and much, much more. The reader is inspired to ponder just what a determined nation of people could achieve if they weren’t trying to fight (or in Attlee’s case, recover from) a war at the same time.

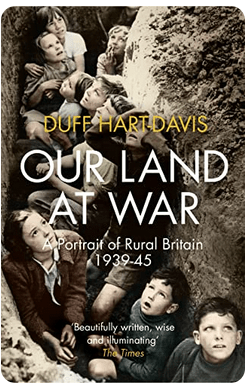

Our Land At War by Duff Hart-Davis. Highly recommended for both entertainment and think-food – it’s got some smashing photographs, too.

********************

Dear Reader,

Times are hard, and so the articles on this site are freely available but if you are able to support my work by making a donation, I am very grateful.

Cheers,

Kay

********************